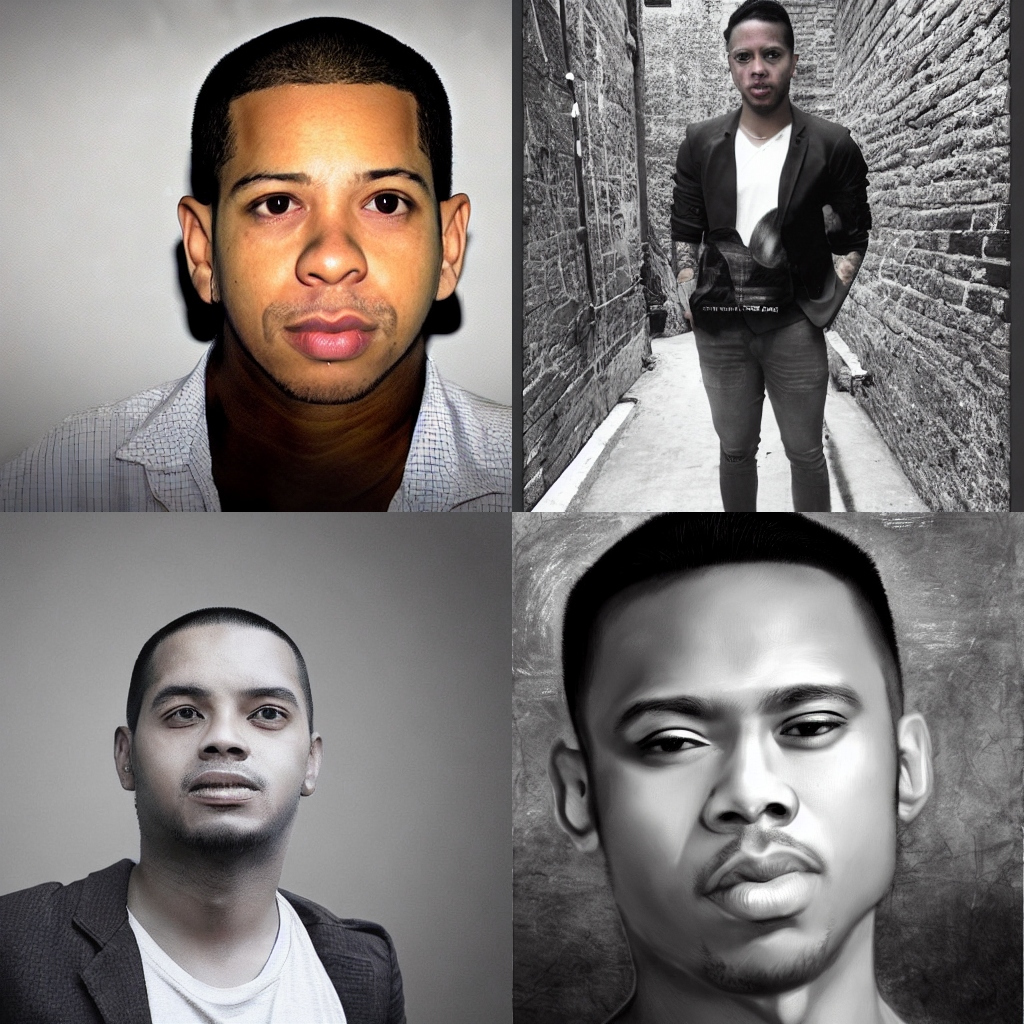

Raymond Freitas, co-author of the study, presented his findings today at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston. “It’s about human behavior,” Freitas pointed out. “Our expectations for our personal behaviors get so high that we overreact.” This reaction to stress affects the health of the human brain at a far greater rate than other factors, and is one of the most dramatic consequences of a chronically under-stimulated brain. Although there is a link between stress and depression, mental health experts believe this connection is primarily a symptom of the underlying brain dysfunction. To find a drug to cure this underlying brain disorder – and prevent additional stress-related disorders – Freitas is pursuing an ambitious research undertaking involving hundreds of subjects that he said should last for years.

“We want to find a drug not only to put people under stress, but to actually stimulate and reverse the brain stress response,” he said, emphasizing that such an effort is both more complex and long-range than most researchers would like to consider. “I’m really a believer in the idea that brain scientists take a more systemic approach to understanding how brain damage can lead to psychiatric disorders.” Scientists have long believed that stress – especially through stressors (like financial loss or a breakup) or interpersonal conflicts – leads to altered connectivity within the brain. There is increasing evidence that this altered connectivity, in turn, leads to a whole host of physical symptoms, including depression and anxiety, as well as mood symptoms of depression and anxiety disorders. Some researchers have argued that such symptoms are caused by physical changes in the brain, while others speculate that the altered connectivity caused by stress is instead driven by hormonal changes in the body. This theory, however, has remained controversial. Freitas intends to investigate the links between psychological stress and altered brain connectivity as part of his project. “We are studying these links in a wide range of stressors, so to look at a single brain event that leads to a depressive or anxiety symptom is too simplistic as an understanding,” he said. “But if we can identify what triggers these changes – specifically which stressors make people more vulnerable to developing depressive or anxiety disorders – then we could use that knowledge to help diagnose or treat these disorders. I think these are important studies that should be encouraged.” Freitas emphasized that the research is both extremely ambitious and long-awaited due in large part to his pioneering work on depression. He hopes that by pinpointing the underlying mechanisms